Business Process Management is a management discipline that thrives to improve process performance. If done right, BPM leads to appealing, user-friendly processes that provide information about productivity, that measure performance and that illustrate the potential for improvement while indicating the exact location in the overall process that potentially benefits from one of various process optimization strategies.

To deal with the complexity of modeling a company's business processes, business analysts proceed hierarchically and begin by describing a value chain (process level 0) through several levels of processes, until they reach a level on which they depict a detailed description of the activities of process participants. Figure 1 gives an overview of BPM with a figure for each modeling technology and the interaction with SOA services.

We see that Business Process Management and SOA go hand in hand: SOA enables BPM.

Figure 1: BPM and SOA: the bigger picture

At the highest level of the process hierarchy, the functional process blocks for end-to-end processes that potentially span departments in the overall organization are described in a high level, very abstract and coarse grained language, like IDS Scheer value chains. There is no branching, but they do include the most important business goals, ideally expressed as KPIs and other organizational aspects, such as assigning steps to departments.

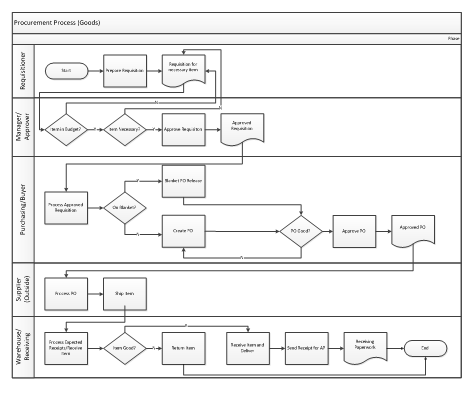

At the next levels, the process steps are described hierarchically, with the level of detail increasing downward. This is done today in the lingua franca for business process models, Business Process Management and Notation (BPMN). Here the process participants or players in a process are represented as "swim lanes," which contain the process steps that are assigned to this participant.

At a middle hierarchical level (levels 1-3), the process participants are still included relatively roughly through the organizational units, such as the "Purchasing" department.

If you drill down deeper into the process details, you reach the fine-grained level (level 4), at which the activities of the process are represented through automatic system interactions via services and through human interactions These steps that are performed by individuals are called "human tasks." Tasks are specified through process participants in their task lists. The sequences within a task can be modeled and listed in detail in an enterprise portal as "page flows." Examples of human tasks are:

- Recording of contract data by dealers or by customers themselves.

- Manual review of a large customer contract

- The receipt of a complaint in the call center

- Handling of an error from a fully-automated process

When designing the human tasks, it is a good idea to distinguish the level of each process participant's expertise and adapt the screen layout accordingly.

- For beginners, a strict requirement of a predefined sequence of linearizable mini-screens that work towards achieving the human task's goal.

- For experts, a greater degree of freedom in the screens' layout appropriate for a modern expert system.

Once a human task's goal has been attained, a SOA service, typically a task service, is called, which writes the data that was collected during the work step transactionally into a persistent store.

Now we have described the interaction between SOA and BPM. Attentive readers will have noticed an alternative to BPMN in the figure. What is hiding behind the new buzzword ACM (Adaptive Case Management), and how does it relate to "traditional" BPM?

We begin to grasp that further increasing efficiency is no longer achieved by further automating routine tasks (that is already mapped in today's standard ERP software). It is rather a question of determining certain tasks that would benefit from the creativity and decision making abilities that differentiate us humans from algorithms. These activities, such as deciding on a customers credit worthiness or prioritizing actions to resolve a critical situation are assigned to knowledge workers. Let us investigate when this new type of process improvement strategy and according role can be applied, where it is best used to complement routine work.

Why is BPM Not Being Enthusiastically Embraced?

Champagne bottles are opened - the business unit employees are happy. They celebrate that in the new BPM project they see to their delight that in practice the process for engaging external employees is running exactly how they specified it in their sequential process model. In detail, this process comprises a variety of assessments and approvals at different management levels. The exact sequences could be very well expressed in the business process model and notation (BPMN) 2.0 modeling languages. These models are understood by everybody in the team and can be easily changed. At the same time, these models are the basis for conforming executable IT processes.

Such success stories in which a departmental workflow has been used successfully in order to improve productivity can be found in most enterprises today and suggest that BPM as whole is a success. They nurture the belief in business IT alignment through BPM. But why is BPM not being more enthusiastically embraced? Why are automated processes not finally breaking away from the limited space for improvements at micro level, or within departments, and pushing forward into the enterprise area? In part the answer lies in reluctance on changing the culture from a siloed approach in which departments are defined through their function and not through their position in the end to end process to an enterprise wide process driven approach. Yet, in the last years it became clear, that flowcharting-based approach as advocated by most current BPM solutions is not sufficient to cover all types of processes. Sometimes it's not feasible to predefine every step before running a business process. Sometimes you don't know what happens next. Sometimes it's best to rely on a human in the field in order to find the right path towards reaching a business goal.

Routine Work vs. Knowledge Work

Increasing efficiency by automating processes – human history did not need to wait for computers in order to materialize this mantra. Henry Ford and Frederick W. Taylor successfully defined a management approach that broke work down into simple tasks, to enable the complexity of the overall job to be managed. In this way, the giant task of manufacturing a car was broken down into many individual subtasks that only required a few movements each. Each production worker had to carry out precisely defined steps. There was no room for acting independently—and it wasn't necessary either.

Drawing on Taylor's vision, several authors in the field of BPM management discipline have been promoting flowcharting as a way to optimize of business processes since the 1980s. These kinds of "normative" BPM projects ideally enable business departments to analyze business processes, document them, and easily change them if needed. However this only functions well for "normative processes" whose flow can be precisely described before being executed.

In knowledge-intensive contexts, this kind of process is too inflexible to be able to map the complex reality. It would simply be too expensive, and ultimately unmaintainable, to model all conceivable variants of the process cycles, including all possible error and event conditions in advance—if you could ever really achieve completeness at all.

A further requirement for successful normative processes is that the people who take part in the process can work productively under close and strict management conditions. Today, the factory of this type of production workers isn't a physical one anymore, but a mental one: They sit in front of their computer screens, forced to go through the same old task lists and screen sequences by process "straitjackets" of predefined processes. This makes it difficult, or even impossible to work in a way that is innovative and suited to the situation.

The process participants are taken by the hand and guided through a given process, following the model. Just like workers on Taylor's assembly line, they have little scope for decision-making.

However, today we have transformed into a knowledge society. Tasks such as customer complaint management, processing damage claims, supporting job hunters, assessing legal issues, or research and development all require a high degree of dynamic reactions, due to their complex circumstances and new events which can occur unexpectedly. Big names in management such as Peter F. Drucker and Thomas H. Davenport describe the rise of the knowledge worker, who is proving to be far less controllable than the production worker.

The Evolution of BPM - From Normative to Adaptive Processes

What impacts are the differing approaches of the production worker and the knowledge worker having on the designs of BPM initiatives? Rigid, or normatively designed processes, which define precisely how a process is to run before they are executed, are suitable when the goal is to standardize work in Taylor fashion. Traditional process automation lends itself to tasks that should always be done the same way in order to standardize quality, such as preparing proposals, applying for vacation days, soliciting legal approval, maintaining IT systems, performing integration, etc. often they are not characterized by a high level of risk.

In many other cases, when things get a bit more critical and involve human decision making, potentially under pressure, normative processes are simply too rigid. It is not always clear how many steps are needed and precisely what paths you should take to reach a goal. This is true, on the one hand, for knowledge-intensive processes, but on the other hand, also for the core processes in the company for which special experts are brought in. Typical examples of this include consulting or sales meetings, assessing an accident, appraisals, and investigations. Here, the focus is on expertise and the individual choice of the subtask by the user, so as to be able to optimally conclude a business transaction.

The attempt to continue to support this kind of knowledge work with normative processes leads in reality to process bureaucracy (everything is fine if the process is complied with, even if the company makes losses), and to ultimately unproductive process instances, as it is not possible to adapt based on experience. We don't need Taylor's approach here. A BPM that supports goals, something adaptive, would be significantly more productive. We are introducing the term "adaptive processes."

Adaptive Processes as a Branch of BPM

In BPM circles, this desired behavior is called "adaptive case management" (Figure 2). You don't look at the processes themselves, but rather focus on the case for which a goal is to be reached, for which a number of possible processes or process steps, depending on the situation, can be executed. Such a case could be anything: an insurance case, a patient, a project, an asset (such as a building), a customer inquiry, or even the entire customer. We consider the term "case" to be too limiting, and are therefore expanding it to include any kind of activity that requires a knowledge worker to be flexible.

In books and the blogosphere you will often find a debate on BPM versus ACM. We motivate instead that BPM is a cross-management discipline that aims to optimize processes. "Normative BPM" (nBPM) and "adaptive BPM" (aBPM) represent two equal approached under the umbrella of BPM, and are therefore useful tools in the toolbox of business and IT architects, which are used depending on the environment and the forces. A process can contain "island" of structured flows and other islands of rather less structured combination of activities. Even then, an ACM island might contain a Flowchart island.

Figure 2: ACM and BPMN are variants of BPM

ACM is a sign for a recognition that IT evolves into providing knowledge workers with an optimal workplace that allows them to make the best possible decisions for the company. This means that people have to be the focus of business process management initiatives again—as participants in the process that are not fully controlled by the process model, but contribute actively and directly to the improvement. We do recognize that this kind of new twist that is not applicable for all works scenarios. Typically it is best used for aspects of business processes that that are not fully standardizable and provide a high degree of risk. An example is the credit decision process in banks. Depending on the type of the credit, this can be a highly standardized process or a rather adaptive type in which the decision-maker is provided with a high degree of autonomous decision-making authority, that will be prohibitive for the highly structured simply credit products.

Modeling Adaptive Processes

The basic idea behind the traditional BPM procedure, here referred to as normative processes, is that a process is a previously defined sequence of activities. All transitions between activities are also predefined. The gateways to processes are based on automatically executable business rules. Human interaction is through entries in work lists, through which the process participants are assigned tasks. All conceivable variants of the process are defined through the gateways (BPMN gateways). It is impossible to proceed in a way that diverges from the overall process model. Figure 3 illustrates this.

Figure 3: BPMN processes precisely describe the work with algorithms

But what happens with adaptive processes? Does chaos rule? How can the business department ensure knowledge workers have free rein, but still perform essential tasks? Adaptive processes do not in any way mean that everything should be left to the user—there are simply more degrees of freedom. Here too activities are defined, but there is the option that allows workers to adaptively incorporate additional human tasks. The transitions between the activities are also not modeled in a fixed way, but are determined at runtime by the individuals taking part in the process. If necessary, they are also supported by rules that can be declared as preconditions. These rules recommend users a list of conceivable activities and tools for the current context.

Living Knowledge

Adaptive processes are in a permanent state of learning and developing. This is what makes them stand out from ad-hoc or dynamic processes, which give the user a great deal of freedom in the form of arbitrarily executing steps or predefined sequences, but do not have any built-in means for optimizing through experience in the process. Adaptive processes give knowledge workers the possibility of defining additional process steps driven by the situation. This helps them to expand the knowledge base and thereby to generate sustainable added value. This results in a permanent adaptation to reality. Despite all the freedom, the path that process participants take is logged, as a basis for permanent process optimization by business units and IT. In particular, suggestions for improvements by the process participants are logged and regularly assessed. This is referred to as model afterwards or design by doing. The ultimate process arises after the fact out of the diversity of the specific instances that have been run.

An essential property is that the semantic relationship between process steps can only be defined to a very limited extent, according to the system of rules that is contained in the BPMN language instructions. These rules also only apply to steps that follow on from each other, in other words it is not possible to express the relationship of remote steps ("Only execute step 19 if step 4 was not run").

Here ACM potentially offers a fundamentally more productive opportunity to describe the technical details of processes. An ACM model describes the semantic relations that activities have with each other. These types of relations express whether an activity must, or can, be completed in advance. These activities are not automatically processed at previously defined times and places in the process pattern on the basis of a process model. Rather, all activities are made available to users as proposals and users can then decide whether and when they make use of them. The model can also be used to specify that a subsequent activity must always be executed after a certain activity. This means that it is possible to map the regulatory policies of an enterprise and, at the same time, to give users the greatest possible degree of freedom. Several approaches to such kind of ACM modeling emerge, with OMG's CMMN, Case Management Modeling and Notation, being a promising one.

Type of User Management and Interfaces

Typical user interfaces in the BPM environment comprise work lists in which users find their tasks assigned by processes. Here, small screens are often supplied for data input in the individual tasks, displayed in a generic UI area.

User interfaces for adaptive processes also provide knowledge workers with a more flexible IT support. Here there are of course also task lists—but the focus is not on executing one small micro step in a large process sequence, but rather on the complete activity. This means we tend to find interfaces which are more like portals, representing an aggregated overall view of the case. For example, all the assigned master data, histories, and previous business cases can be found here. If it is a patient system, you, as the patient, are the "case," including your entire medical history, all examinations on file, examination reports, X-rays, etc. This makes it clear that accessing unstructured data, such as on a document management system, is an important feature of the interface. However, social and collaborative features and generally all activities that could be meaningful in the context, should also be available at all times. Then there are situations in which the process participant needs to create a new activity that has not been anticipated and where no software exists at all. This is an ad hoc activity, imposing the need for ACM tools that allow to adaptively add new activities to the case that were previously not considered.

Reclaim the Grey Zone

Adaptive Case Management is still evolving. We just start to grasp the future of work. This is a future in which we decide whether algorithms take control over important decisions such as a credit worthiness check or whether we reclaim the grey zone, the moment in which the algorithm says "maybe" and leave the final word to the human expert.